Philosophy stack

The goal of this page is to try to gather a large quantity of public domain primary philosophical sources, which despite their antiquity can be difficult to find, especially in the same place. The overall theme of the works involved are broadly about what we would call today physics and mathematics, although in a rather broad manner. Included are books on physics, astronomy, ontology, metaphysics, geometry and logic. Unless part of a book on one of those topics, I will probably not include any books on biology, ethics, the human soul, the gods, politics, good living or the arts.

As many of those books are very reliant on the understanding of the era, they typically come with rather lengthy introductions on that topic in modern editions. I have for the most part just included the raw text (or at least what we have of it today), with some of my own notes on the topic. Links to more historical oriented versions of those books will be included if possible if you wish for more details on the matter. I have also chosen not to keep some elements of mainly historical importance, such as line numbers.

Many of these texts (and more) can be found on the following sites :

The timeline

To give some notion of the general ordering of those various sources, here's a rough timeline of the philosophers involved :

Sources

- Aristotle - Metaphysics

- Aristotle - Physics

- Aristotle - On the Heavens

- Archimedes - The Sand Reckoner

- Sextus Empiricus - Against the Professors

Geography

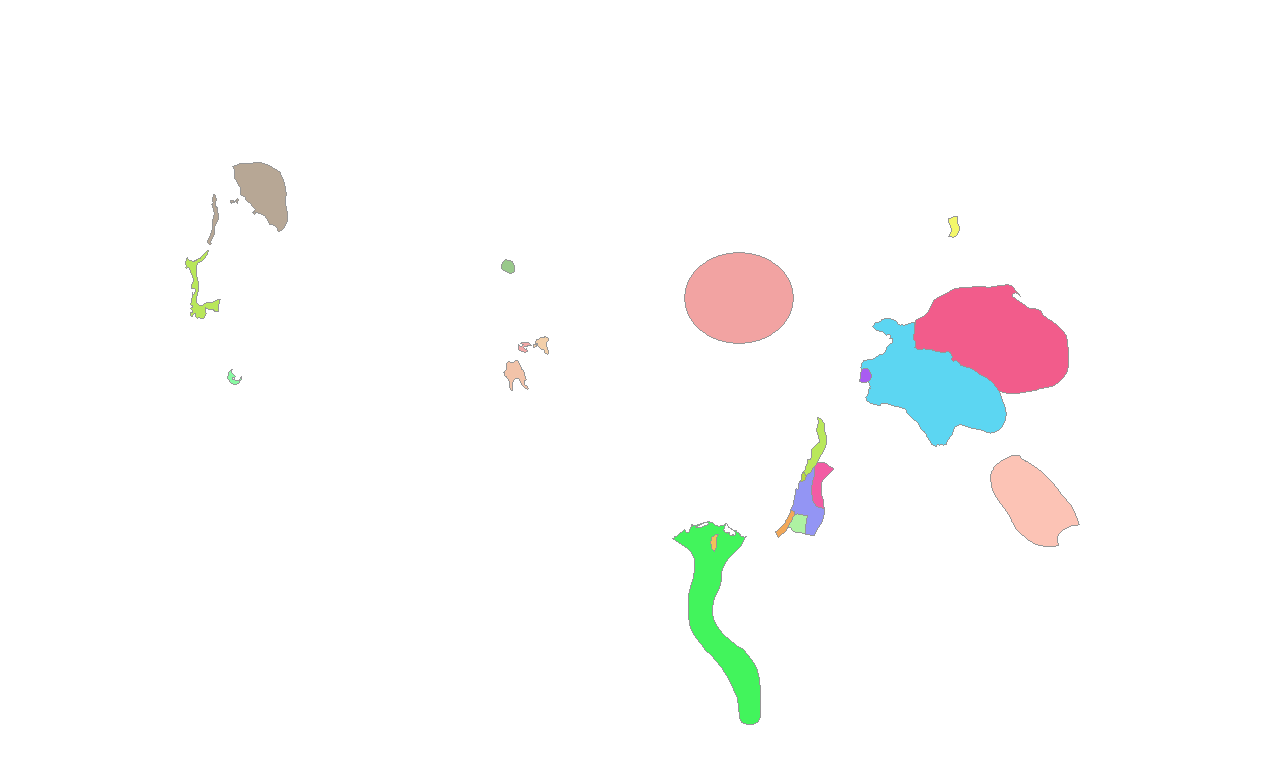

The following map shows the approximative location of each philosopher of antiquity through time. As with the previous timeline, note that there are quite a lot of unknowns, the dates of both the philosophers and the polities representing just the best historical reconstruction of those, and that for the most part they represent the entire life of the philosopher and not just their working years, which are typically unknown. I have tried to keep the location of specific philosophers through time (such as Pythagoras moving from Samos to Croton), but this is still rather approximative, and I did not include extra locations which are either irrelevant (ie. early youth) or of unknown dates, such as mentions of "travels" (Pythagoras again, claimed to have travelled all over the world).

A few of those locations (such as Sextus Empiricus or Cleomedes) are fairly speculative and tend to be based on rather disputable elements such as "The current city where philosophers would likely live during that era".

For clarity, cities are only included after their founding and before their collapse, and they might also not be included if they lose relevance. The city of Mytilene after Epicurius lived there is not important enough to mask the presence of the Kingdom of Pergamon. Small towns near larger towns (such as Pitane near Smyrna) are also not included to avoid obfuscation.

(The source of the maps of the era are from GeaCron.)

Sociology

An interesting lens that one can look at the various individuals invested in this early form of science is the socio-economics classes to which they generally belonged.

This is made somewhat difficult by the variety of cultures involved, going from bronze age Mesopotamia to late antiquity Eastern Roman Empire. But to give some idea of the structure, let's give a look at the economic classes of Ancient Athens.

The constitution of Solon for Athens split (for tax and military purpose) the population into four classes, based on some measure of what their estate produced in terms of "measure" of some goods (grain, wine or olives) or equivalent.

- The Pentakosiomedimnoi (Πεντακοσιομέδιμνοι), earning over 500

- The hippeis (ἱππεῖς), earning between 300 and 500

- The zeugitai (ζευγῖται), earning between 200 and 300

- The thetes (θῆτες), earning less than 200

Outside of this were the other non-citizens of Athens, such as the women, slaves and foreigners.

While we do not have the classification of each philosopher in this system, we can try to

Determining the exact class of each individual can be complicated, as for a large majority of them, we have no or nearly no biographical details, and for the rest, a large amount of it may come from unreliable sources, such as Diogenes Laërtius' Lives of Eminent Philosophers[1]. The amount of details we have also differs. To try to get the general social class of the individuals, I have picked either the profession or actual class of the individual (outside of their philosophical profession and related, such as teaching at some philosophical academy), or that of their parents.

If we look at the Assyrians (and successor states like Babylon, Persia, the Seleucid empire or Parthia), the main individuals we have are mostly members of the hereditary priesthood of various temples.

In Greece, the situation is a bit more complex. During the pre-socratic era, they all seem to be firmly in the upper class, even the nobility, for those that we know of. Thales is said to be a descendent of Cadmus, legendary founder of Phoenicia. Heraclitus is said to have renounced his kingship in favour of his brother. Parmenides is said to be "of illustrious birth and possessed great wealth", Zeno of Elea was said to be Parmenides' adopted son, Melissus was elected admiral, Empedocles is "of an illustrious family", Protagoras was a famed sophist and Hippocrates of Chios was, while having lost his fortune, originally a wealthy merchant. Pythagoras' father was said to be a gem-engraver

...

One possible issue with this analysis is that there is a marked split in available informations between philosophers propers, which typically have at least some informations on them available (although for many of them this is all from the only surviving large text on the topic, Diogenes Laërtius' Lives of Eminent Philosophers), and people who seem to be more narrowly focused on mathematics, astronomy or mechanics, with little other known philosophical topics to their credit. The distinction is difficult to make due to the general lack of informations, and the difference is not quite clear. Many of those people were still said to be the teachers of other philosophers, for instance. While it is possible that they are merely philosophers whose other accomplishments have been forgotten, let's still see the difference.

If we do a rough split between those two categories, about 40% of the philosophers seem to not have any biographical detail that could tell us of their class explicitly (such as Anaximander, Anaximenes, Democritus, Sextus Empiricus, Plotinus or Porphyry). For the mathematicians, astronomers, etc, this number rises to 84%, many of those who have any details being from the earlier era. A lot of those individuals being affiliated with Alexandria (see below)

Institutions

One important lens through which to consider the geographical and historical distributions of the philosophers that we have seen is the institutions which mostly constituted those people. There is often a certain sense by which it is considered that ancient philosophers were for the most part individuals not formally associated with each other, informally as schools of thoughts like the Stoics, Epicurians, etc, and while that is certainly one way that this happened, there was also quite a lot of formal institutions for it.

The Mesopotamian priesthood

The first major institution involved with scientific matters in this list is the priesthood of the Neo-Assyrian empire. There were equivalent institutions in Assyria and the various Babylonian empires beforehand as well, as can be seen in the MUL.APIN (𒀯𒀳) star catalogue, but this period seems to have little in the way of mentions of specific individuals. On the other hand, we have a much better overview of the priesthood in general in the Neo-Babylonian period. For these reason, I will try to give a hopefully coherent general overview of the priesthoods in Mesopotamia in general during that period.

The priesthood we have seen

- bārû (𒇽𒄬) : diviner

- kalû (𒊩𒄸) : lamentation priest

- āšipû (𒅗𒅲𒅅) : exorcist

- šangû (𒋃) : high priest

- šangû šanû : deputy priest

- išippu : purification priest

- ērib bīti : clergy/temple enterers

- šešgallu : high priest

" the king had a duty to support and patronize the temples in his empire, and temple rebuilding, sacrifices, and royal rituals are highly visible in the official texts. Ritual texts, which give some insight into cultic practices, also focus mostly on the responsibilities of the king, though at least professional priests are mentioned; however, rituals do not provide information about priestly duties outside of that particular context."

"Reports were sent from many places in Assyria and Babylonia to the capital. In this way conditions unfavorable for observation could be overcome: if obseıvation was impossible in Nineveh because of clouds, it may have been performed successfully somewhere else. In a letter of Bel-usezib (RMA 274) it is taken for granted that an eclipse not observable in Nineveh will have been seen at some other obseıving post, and the following cities are enumerated where one should ask foı information: Assur, Babylon, Nippur, Uruk, and Borsippa.

Some senders of Reports give their place of origin after their name at the end of the text; while this is not necessarily the place at which they observed, it is the most likely place. In connection with the names, the cities of Assur, Uruk, Borsippa, Dilbat and Cutha are mentioned. A thorough investigation of the places from which Reports were sent can be found in Oppenheim's article. From this it appears that Reports were also sent from Babylon, although none of the reportels is explicitly called "from Babylon" in his name.

On the topic of the role of priesthood, we know that the Egyptian priesthood had similar roles regarding astronomy, cf. for instance in Strabo's Geographia. We have much fewer names in details and I have only included Harkhebi in the list which seems to be fairly well corroborated. Other names do exist such as Sonchis of Saïs, Chonuphis and Oenuphis of Heliopolis, but those are fairly late accounts without any details given.

The priests devoted themselves to the study of philosophy and astronomy, and were companions of the kings.

The Platonic Academy

The first formal academic institution for what we could call scientific matters today was the Academy founded by Plato around

The Peripatetic school

The Alexandrian institutions

One major ancient institution in antiquity was that of Alexandria, constituted mainly by the Museon and the Library of Alexandria.

The library was founded, depending on the source, either by Ptolemy I Soter or Ptolemy II Philadelphus. This can be read for instance in The letter of Aristeas

Demetrius of Phalerum, as keeper of the king's library, received large grants of public money with a view to his collecting, if possible, all the books in the world; and by purchases and transcriptions he to the best of his ability carried the king's purpose into execution. Being asked once in my presence, about how many thousands of books were already collected, he replied "More than two hundred thousand, O king; and I will ere long make diligent search for the remainder, so that a total of half a million may be reached.[...]"